The Blankets of Honesty

- By Jacob Allred

- •

- 07 Dec, 2018

- •

by Frances Burk Perry

The Blankets of Honesty

Discover the joyful true tail of Jacob Hamblin and the

Blankets of Honesty from Perry Tales.

This book from Perry Tales can be purchased on Amazon.com by clicking "here".

Learn more about this true tail in The Friend Magazine, July 1987 on lds.org by clicking “here”.

Jacob Hamblin, Trustworthy Pioneer

They were men who were true at all times in whatsoever thing they were entrusted (Alma 53:20).

Jacob Hamblin was a brave pioneer who showed his courage by always telling the truth. The Indians knew that he was fair and honest, that they could trust his word. On one occasion Jacob was confronted by twenty-four Indian warriors who believed that the Saints were responsible for the deaths of three Indians. They wanted to take Jacob’s life, but he told them that his people had not betrayed them. After eleven hours of debate, the Indians decided to settle the matter peacefully because they knew that Jacob Hamblin had never lied to them. (See Valiant B Manual, page 140.)

Here are pictures for another true story that shows how Jacob Hamblin could be trusted. Cut out the characters and mount them on flannel. Place them on a flannel board as you read what each one says. You could give the story as a play for family home evening and have family members read assigned parts. The characters could be attached to tongue depressors or Popsicle sticks and held by each person.

The

Trade

Jacob, Jr.: I am the son of Jacob Hamblin. My name is also Jacob. One day my father sent me to trade a horse for some blankets with an old Navajo Indian chief.

Jacob Hamblin: I am Jacob Hamblin. I told my young son to be sure to make a good trade.

Jacob, Jr.: I rode on horseback, leading the horse that was to be traded.

Navajo Chief: I am the Navajo Indian chief. Young Jacob told me that his father wanted to trade a horse for some blankets. I brought out a number of handsome blankets.

Jacob, Jr.: I shook my head and said that I would have to have more.

Navajo Chief: I brought out two buffalo robes and quite a few more blankets.

Jacob, Jr.: Thinking that I had done quite well, I bundled all the blankets and robes into a roll behind my saddle, mounted my horse, and started for home.

Jacob Hamblin: When my son arrived home, I undid the roll of blankets and robes. I looked at them and began to separate them. I put blanket after blanket into a pile and then rolled them up. I told young Jacob to take them back and tell the chief that he had sent too many.

Jacob, Jr.: I rode again to the Indian chief, returned the blankets to him, and told him that my father thought that he had sent too many. The old chief smiled and said:

Navajo Chief: I knew that you would come back; I knew that Jacob would not cheat me. (Adapted from Valiant B Manual,page 139.)

Sharing

Time Ideas

1. Scramble letters of word pioneer. Ask children to think of word that describes someone who is brave, prepares the way for others, or does something new. Then tell true story “The Trade,” using flannel board figures. For large group, cutouts could be prepared for overhead projector.

2. Prepare copies of figures for each child to cut out. (Older children could cut out figures for younger ones.) Divide children into groups of four to six. Have each child choose figure; each group then retells story among themselves.

3. Three people could dress as characters of story. Use blankets for props.

4. Sing “Whenever I Think About Pioneers” (Sing with Me, E-2, verses 1, 2, 5, and 6).

5. Discuss situations in which people show trust. Make chart listing examples from scriptures, examples of people whom children trust, and examples of people trusting children.

https://www.deseretnews.com/article/700028163/Dead-ringer-or-dead-on-Jacob-Hamblin-photo-mystery.htm...

CEDAR CITY — Family history is wearing many faces, from the new FamilySearch to a barrage of television shows geared at the rediscovery of roots.

But some of the greatest family history adventures still happen under your own roof, sometimes by accident, sometimes through a moment of inspiration.

Kathryn Ipson's son, James, was doing research on Jacob Hamblin, best known in LDS church history as a liaison to the Native Americans when the pioneers settled in the West.

A Google search yielded a solitary photo of Hamblin: His mouth pulls down at one corner, his chin is nestled in a thick goatee, and his hair is smoothed back from a broad, square forehead.

James shared the photo with his mother. Something about it made Ipson, 74, take pause.

"Let me show you an old daguerreotype I have," she told James.

She pulled a photo from a box and the two huddled over it. The image of a striking man with a thick goatee, his hair smoothed back from a broad, square forehead, stared up at them … and they stared back in amazement.

"We suddenly realized it could be an earlier photo of Jacob Hamblin," Ipson said.

The real research, and a real mystery, began for Ipson and her family.

More than 20 years ago, Ipson's sister, Carol Dodds, 77, had given her the photo. Neither sister was familiar with it — Dodd merely knew that Ipson liked old trinkets.

Ipson tucked the photo safely away, attaching a note to it that read: "I have no idea who this is a picture of." She promptly forgot about it.

Upon its rediscovery, Ipson found out the photo is actually an ambrotype — an early type of photograph made by imaging a negative on glass backed by a dark surface. The technique became popular in America in the 1850s. One of Ipson's first questions was, "Did they even have ambrotypes in Utah that early?"

She was able to talk to Nelson B. Wadsworth, author of "History of the Mormons: In Photographs and Text, 1830 to the Present," who confirmed that the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers have ambrotypes from the late 1850s and early 1860s.

Ipson showed the ambrotype to Brent Ashworth, document expert and owner of B. Ashworth's bookstore, which is dedicated to rare books, manuscripts and other collectibles.

"To me, it looks just like Jacob Hamblin," Brent Ashworth wrote via e-mail. "I believe it is a wonderful new view of this great pioneer (and) 'apostle to the Lamanites.' "

"I took (the photo) to the Jacob Hamblin home in St. George and showed it to them," Ipson said. "I also took it to the BYU Library, the Church History Library … Most people believe this is of Jacob Hamblin."

Ipson and Dodd have stewed over the ambrotype's origin. Their family is from Panguitch, where Hamblin had relatives settle. Dodd is also related by marriage to Ira Sterns Hatch, one of Hamblin's mission companions.

Dodd wonders if she acquired the photo years ago when a friend was cleaning out an abandoned storage shed in St. George. He left a box full of papers and old photos on Dodd's doorstep since he knew of her enthusiasm for family history.

Thanks to such enthusiasm, Ipson and Dodd have at the very least enjoyed the research. Ipson has even compiled possible dates the photo could have been taken, based on reading various books on Hamblin.

"For me, the best thing that has come from this is getting to know (Jacob Hamblin)," Ipson said. "What a peacemaker and dedicated man he was. I hope that more people will visit his home in Santa Clara and read some of the books available about him."

Ipson also hopes others will be inspired to start combing through their old papers or photos. You never know what — or who — you might find.

--

During the 2019 Jacob Hamblin Family Reunion in St. George, Utah, hosted by the Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization, Wade Wixom, Hart Wixom's son spoke and also shared this picture. Wade's opinion was this photo is a genuine photo of Jacob Hamblin. He felt it in compairing the verified photo the church has and this new one that the new one was Jacob before he fell out of a tree and injured himself and was taken when Jacob was younger. See the reunion footage from the Jacob Hamblin Legacy Organization for more details.

November 1863. Jacob Hamblin had just left his home in Santa Clara to get supplies in nearby Cedar City, Utah. Two Indians rode up to the Hamblin home and angrily demanded: “Where is Jacob?”

When they learned he had gone to Cedar City, they dashed off in that direction with their horses. Overtaking Jacob, they called for him to stop.

“We have come to kill you!” they called angrily.

For a few moments there was silence. Then Jacob climbed down from the wagon seat, looked at the Indians, and pulled his shirt open—as if to say, “Shoot, I am unarmed.”

The Indians stared a moment in silence. Then one muttered: “Can’t Jacob, you’ve got my heart.” They rode away. 1

Jacob Hamblin. At a time when few white people were trusted, the Indians looked upon Jacob as a true friend. Today he is considered the most influential and successful peacemaker and missionary among the Indian people in the territorial period. 2

He was a man totally committed to God and to the building up of God’s kingdom among the Indians. “Although Jacob Hamblin generally carried a gun of some sort,” writes historian John Henry Evans, “his dependable weapon was prayer and the most absolute trust in God. … He ate with the Indians, he slept with them, he talked their language, he prayed with them for the rains to save their crops … , he thought their thoughts, … till he knew more perhaps than any other American ever knew of the native, and exerted far more influence with them.” 3

Jacob Hamblin was born in Salem, Ohio, on 2 April 1819 to Isaiah and Daphne Haynes Hamblin. He married Lucinda Taylor in 1839 and they made their home in Spring Prairie, Wisconsin. Three years later, in February 1842, he attended a meeting where the missionary Lyman Stoddard was preaching. “I shall never forget the feeling that came over me when I saw his face and heard his voice,” Jacob relates. “He preached that which I had long been seeking for; I felt that it was indeed the gospel.” 4 He was baptized 3 March 1842.

Jacob served as a missionary for a short time, but was called home when the Prophet Joseph Smith was martyred. When word came from Church leaders to move west, his wife refused to go. But she told him to go and take the three children with him.

Needing help with his motherless family , Jacob relied on the Lord. In a dream he saw a widow and two children in a log cabin. At the same time a widow, Rachel Judd, had a feeling that her future husband would soon call at her cabin. Jacob went to her home, introduced himself, and explained that he had been impressed to ask her to be his wife. She agreed; they were married on 30 September 1849, came to Utah the next year, and were later sealed in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

Jacob was directed to settle his family in Tooele, Utah. At that time the Latter-day Saints had developed a policy of feeding the Indians to avoid fighting with them. However, the settlers barely had enough provisions for themselves—and giving food to the Indians proved to be a hardship. The settlers also found that their grain and livestock were often stolen.

To combat the increasing thievery, a military company was formed, with Jacob as a first lieutenant. “I asked for a company of men,” he relates, “to … hunt up the Indians. … One morning at daybreak, we surrounded their camp. … The chief among them sprang to his feet, and stepping towards me, said, ‘I never hurt you, and I do not want to. If you shoot, I will; if you do not, I will not.’ I was not familiar with their language, but I knew what he said. Such an influence came over me that I would not have killed one of them for all the cattle in Tooele Valley.”

Jacob wanted some of the Indians to accompany his group back to the settlement. Afraid, but confident in his assurance of safety, they went. When they arrived, a superior officer decided to ignore Jacob’s promise and have the Indians shot.

“I told him I did not care to live,” writes Jacob, “after I had seen the Indians whose safety I had guaranteed, murdered, and … if there were any shot I should be the first. At the same time I placed myself in front of the Indians. This ended the matter and they were set at liberty.” 5

On a later occasion, the Spirit made it known to Jacob in a dramatic way that he was to be a friend and brother to the Indians—a peacemaker—rather than an enemy. “I … secreted myself behind a rock in a narrow pass. … I had not been there long before an Indian came within a few paces of me.

“I leveled my rifle on him, and it missed fire. He sent an arrow at me, and it struck my gun. … ; he sent the second, and it passed through my hat; the third barely missed my head; the fourth passed through my coat and vest. As I could not discharge my gun, I defended myself as well as I could with stones. …

“I afterwards learned … that not one [of our company] was able to discharge his gun when within range of an Indian. … It appeared evident to me that a special providence had been over us … to prevent us from shedding the blood of the Indians. The Holy Spirit forcibly impressed me that it was not my calling to shed the blood of the scattered remnant of Israel, but to be a messenger of peace to them. It was also made manifest to me that if I would not thirst for their blood, I should never fall by their hands.” 6

In the October 1853 general conference, Jacob was called to be a missionary among the Indians in Washington County. The next spring he left for the southern Utah settlement of Harmony, and then in December, he was selected, with other missionaries, to settle Santa Clara.

The Indians in the area were somewhat nomadic, wandering about in search of food. The settlers had scared their game away, they said, and the white man’s cattle ate the grasses, roots, and grains that the Indians depended upon for food. Since the land was theirs, they maintained they were entitled to part of the crops and cattle the settlers produced. The conflict led to a great deal of trouble.

But Jacob had much compassion for the Indians. He developed a great love for them and set about to help them improve their conditions. Blessed by the Lord, he found a measure of success. He and the other missionaries taught the Indians farming techniques so they would not suffer from hunger. “The patient and industrious Jacob Hamblin … may truly be designated ‘the Indians’ friend,’” wrote Thomas Brown, an early settler. “Under his industrious care, I doubt not they will soon be able to raise their own wheat, stock and other edibles, also cotton.” 7

Jacob completed this mission in June of 1855. But when he met with Brigham Young, the prophet told him to take his family, which by then included an adopted Indian boy, back to southern Utah—and he admonished Jacob not to neglect his mission among the Indians.

On 4 August 1857 President Young appointed Jacob president of the Santa Clara Indian Mission. He urged Jacob to “continue the conciliatory policy toward the Indians … and to seek by words of righteousness to obtain their love and confidence.” 8 Jacob worked steadily alongside the Indians and won their trust and confidence. He talked with them in their language, always spoke the truth, and honored all his promises. As a result, he had tremendous influence with them. In later years his personal code of ethics in dealing with the Indians was distributed to all missionaries and others who dealt with the Indians.

He taught his children well by his example. One biographer records: “A son of Jacob Hamblin says that when he was a very small boy his father called him one day and said, ‘Son, take this horse over to my friend, Chief Frank, and exchange the horse for some blankets.’” The boy, eager to prove himself a good trader, returned with an excessive number of blankets. Jacob, seeing the uneven trade, sent him to give back the excess blankets, “whereupon the chief said, ‘I knew my friend Jacob would send you back; he is our father too.’” 9

Jacob continued to work mightily to keep peace between the Indians and the settlers, and to ensure the safety of the many emigration companies that were passing through the area. He had long been curious about a group of Indians called the Moquis. After receiving approval, he organized an expedition and left with a group of twelve men on 28 October 1858. They traveled in a southeast direction, crossing the Colorado River at the eastern end of the Grand Canyon, known as the Crossing of Our Fathers. After a ten-day journey they arrived at the Indian village in northeastern Arizona. Their visit appeared to fulfill a prophecy: “A very aged man [a member of the Moqui tribe] said that when he was a young man his father told him that he would live to see white men come among them, who would bring them great blessings … and that these men would come from the west. He believed that he had lived to see the prediction fulfilled in us.” 10

After sending a report of their trip to Salt Lake City, Jacob received a letter from President Young. The letter told him to take a second expedition to the Moquis and “as soon as they become sufficiently familiar with our language, present to them the Book of Mormon and instruct them in regards to its history and the first principle of the Gospel.” 11 Jacob did visit the tribe again the next year, staying with them several weeks.

In 1864 a group of Indians made raids upon the settlers by the Colorado River. Jacob settled these difficulties and then made two more trips to the Moquis. His second trip extended into March of 1865.

In 1866 Jacob started out on another missionary expedition but became ill and turned back. He sent word to his family, and his wife came and took him home to Santa Clara. He remained in very poor health for a year—his friends believed he was dying. He relates that he was willing to die. But when he heard his little children crying around him, the question came into his mind, “What will they do if I am taken away? I could not bear the thought of leaving my family in so helpless a condition.” 12 He asked for a blessing and afterwards felt a new desire for food. After this he made a slow recovery.

After some settlers were murdered by Indians, Jacob was called to act as a guide and interpreter for a company of soldiers. In 1867 he was called to visit the Indians to the east of the Rio Virgin. “I had many long talks with them,” he relates, “which seemed to have a good effect. Although some of the bands were considered quite hostile and dangerous to visit, I felt that I was laboring for good, and had nothing to fear.” 13

Indeed, Jacob was fearless in the face of danger. For this quality he was much respected, especially among the Indians. He had a way of winning the hearts of the Indians by his honest ways and with his remarkable courage. For example, on one occasion, wrote an associate, “Jacob Hamblin … was captured by the Indians, and was tied to a stake and faggots and other dry wood piled up around him. The purpose then being to fire same and finish him for all time. The Indians then danced about and uttered their war cries with the blood-curdling emphases, but could in nowise shake his inherent bravery, for he smiled and bade them finish the job. The Chief of the Indians was so astonished at his utter lack [of fear, that] they ever after proved themselves in many ways to be his friends and he ever their brother.” 14

Keeping a watch on the eastern frontiers of southern Utah often kept him away from Santa Clara and home, so Jacob decided to move his family closer to him. They moved to the unfinished fort at Kanab, Utah, in September of 1869. Jacob continued to do much to settle disputes between the Indians and the settlers. He went to Kanab and helped the Paiutes plant corn and vegetables, and they held peace parleys together. 15 When President Brigham Young visited the region in April 1870, he told Jacob to continue visiting the Indian camps, maintain peaceful relations, and prevent the shedding of blood. At that time Jacob was relieved of his previous responsibility of guarding the frontier.

A few months later, Major John W. Powell of the United States Geological Survey sought Jacob’s assistance as an interpreter and guide. On September 19 a peace council was held in the Mt. Trumball area. Major Powell relates: “After supper, we hold a long council. A blazing fire is built, and around this we sit—the Indians living here, the shivwits, Jacob Hamblin and myself. This man, Hamblin, speaks their language well, and has a great influence over all the Indians in the region round about. He is a silent, reserved man, and when he speaks, it is in a slow, quiet way, that inspires great awe. His talk is so low that they must listen attentively to hear, and they sit around him in deathlike silence. When he finishes a measured sentence, the chief repeats it, and they all give a solemn grunt.” 16

Jacob explained to the council the reason for Major Powell’s visit, reassuring them that they meant no harm. He told them that the Indians should be friends and help Major Powell find water. The chief of the Shevwits responded, “Your talk is good and we believe what you say. We believe in Jacob and look upon him as a father. When you are hungry you may have our game … We will show you the springs, and you may drink; the water is good. We will be friends, and when you come we will be glad.” 17

Major Powell, aware of the great abilities of Jacob as a peacemaker, asked him to accompany him to Fort Defiance. At that council Jacob again spoke to the Indians: “I have now gray hairs on my head, and from my boyhood I have been on the frontiers, doing all I could to preserve peace between white men and Indians.

“I despise this killing, the shedding of blood. I hope you will stop this, and come and visit, and trade with our people.” When Jacob finished speaking Barbenceta 18 , the principal chief of the Navajos, stood up and walked over to Jacob. Tears started up in his eyes and he put his arms around him, saying: “My friend and brother, I will do all I can to bring about what you have advised.” 19 A treaty was signed as the result of this council.

Sadly, this was broken by a tragedy during the last part of 1873. Four young Navajo braves were returning home when a blizzard arose. They took shelter in an empty home nearby. The storm continued, and, since they had no food, they killed a cow. When the owner heard that Indians had camped in his house and killed his cow, he gathered his friends and attacked the Indians. They killed three and wounded the fourth, who managed to escape.

Jacob, upon learning of the incident, knew that to the Navajos it would appear as a flagrant violation of the treaty. The offenders were not Latter-day Saints but they were in “Mormon territory.” The Indians would consider it a Mormon treachery.

Brigham Young sent word to Jacob to go immediately to the Navajos and explain that Latter-day Saints were not the perpetrators of the Grass Valley incident. Jacob was unable to find a single man willing to go with him on such a dangerous trip and was advised by many to stay home and prepare for war.

“I left Kanab alone,” Jacob writes. “My son Joseph overtook me about fifteen miles out with a note from Bishop Levi Stewart, advising my return.” 20 Jacob, however, went on. Remaining overnight at Mowabby he received a second note from Bishop Stewart, saying he would surely be killed if he went on. But Jacob stoutly says of that occasion, “I felt that I had no time to lose. … My life was of small moment compared with the lives of the Saints and the interests of the kingdom of God. I determined to trust the Lord and go on.” 21

On his journey Jacob met two Smith brothers, who accompanied him. Upon arriving, Jacob found that Chief Hastile, the arbitrator, was not there. The young braves were set upon a blood revenge, but the older ones agreed to talk. One of the Smith brothers relates the following: “Into this lodge was crowded twenty-four Navajos, four of whom were Counselors of the Nation. The Council opened [the second day of talks] by the spokesman asserting that what Hamblin had said the previous night concerning the killing, was false, … that Hamblin was a party to the killings.” The spokesman then recommended death by fire for Jacob. The other two could return after witnessing the torture.

Fully aware of the danger, Jacob “behaved with admirable coolness, not a muscle in his face quivered.” Then he spoke: “I have been acquainted with your people many years, and I have worked many moons to bring about peace … I hope you would not think of killing me for a wrong with which neither myself nor my people had anything to do.” He “challenged them to prove that he had ever deceived them; ever spoken with a forked tongue.”

After his words, which began to soften the feelings of the elder Indians, the wounded brave was brought in and his wounds were exposed. According to one of the Smith brothers, “The sight of the wounded brave roused their passions to the utmost fury. … It seemed that our hour had come. … It was a thrilling scene; the erect proud form of the young Chief as he stood pointing at the wound in the kneeling figure before him; the circle of crouching forms; their dusky and painted faces animated by every passion that hatred and ferocity could inspire, and their glistening eyes fixed with one malignant impulse upon us. …

“The suspense was broken by a Navajo … who once again raised his voice in our behalf, and, after a stormy discussion, Hamblin finally compelled them to acknowledge that he had been their friend; that he had never lied to them, and that he was worthy of belief now.” The council finally adjourned after a tense eleven hours and let the case go before the arbitrator.

Jacob later said in his wry way, “For a few minutes I felt that if I were permitted to see friends and home again, I would appreciate the privilege.” At the closing of the investigation a month later, Chief Hastile said, “I am satisfied; I have gone far enough; I know our friends, the Mormons, are our true friends.” 22

At the end of 1874 Jacob was placed in charge of the Church’s livestock on the frontier and traded often with the now peaceable Navajos. A happy event occurred on the last of March 1875 when nearly two hundred Indians were baptized.

During the winter of 1875–76, Jacob “had the privilege of remaining at home [in Kanab]. My family was destitute of many things. Some mining prospectors came along, and offered me five dollars a day to go with them, as protection against the Indians. … It seemed like a special providence to provide necessities for my family, and I accepted the offer.” 23

He continued in his labors and met with Brigham Young in 1876. At this time President Young gave Jacob a blessing in which he was given special status as an emissary to the Indians. President Young said to him: “You have always kept the Church and Kingdom of God first and foremost in your mind. … You can have all the blessings there are for any man in the temple.” Jacob says of this meeting, “The assurance that the Lord and his servants accepted my labors … has been a great comfort to me.” 24 At this time he was fifty-seven years old.

Jacob moved his family to Arizona in 1878, but he visited Utah regularly to report on his labors in Arizona, and later in New Mexico, where he moved in 1884. During one trip to Utah in 1885, Jacob met with Wilford Woodruff, who was president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles. President Woodruff recognized Jacob’s unusual abilities with the Indians and wrote him a special certificate. The certificate called him to be a missionary among the Lamanites and gave him the right and authority to go into any part of the United States and Mexico to preach the gospel.

The next summer he paid a visit to the home of his son Lyman in Alpine, Arizona. While there he caught the chills and fever. He felt better after two weeks and wanted to go home. On the way back, he and his grandson camped out in the rain in a leaky shelter. Jacob became soaked and suffered a relapse. They camped out another night, and when they arrived home—now Pleasanton, New Mexico—they found everyone ill with malaria. After three days of illness he died, on 31 August 1886. His wife, the only one able to get out of bed, was assisted by some strangers in burying him. His body was later reinterred at Alpine, Arizona. On his gravestone are the words “Peacemaker In The Camps Of The Lamanites.”

Jacob’s devotion to the Church was unfaltering. His faith and trust in God was absolute. And throughout the years, his love and dedication to his family was always a motivating force. Life was never easy for them. But their sacrifices and their loyalty to one another made it possible for Jacob to accomplish all that he did.

Pearson Corbett, one of Jacob Hamblin’s biographers, says of him: “He loved President Brigham Young and the Prophet Joseph Smith and accepted them as direct emissaries from God. … His devotion and loyalty to his Church, his God, his family and fellow associates places his name high among his contemporaries and will be remembered among his people for generations to come.” 25

Frederick S. Dellenbaugh, an explorer and member of the Powell Colorado River Expedition, said of him: “Old Jacob was a remarkable character, and must hold a place in the annals of the Wilderness beside Jedediah Smith, Bridger, … and the rest of that gallant band. But he differed in one respect from every one of them; he sought no pecuniary gain, working for the good of his chosen people. … Old Jacob was one of the heroes of the Wilderness, and one of the last of his kind.” 26

Illustrated by Don Seegmiller

Notes

-

Marlene B. Sullivan, a free-lance writer and mother of five, is a member of the North Logan Fifth Ward, North Logan Utah Stake.

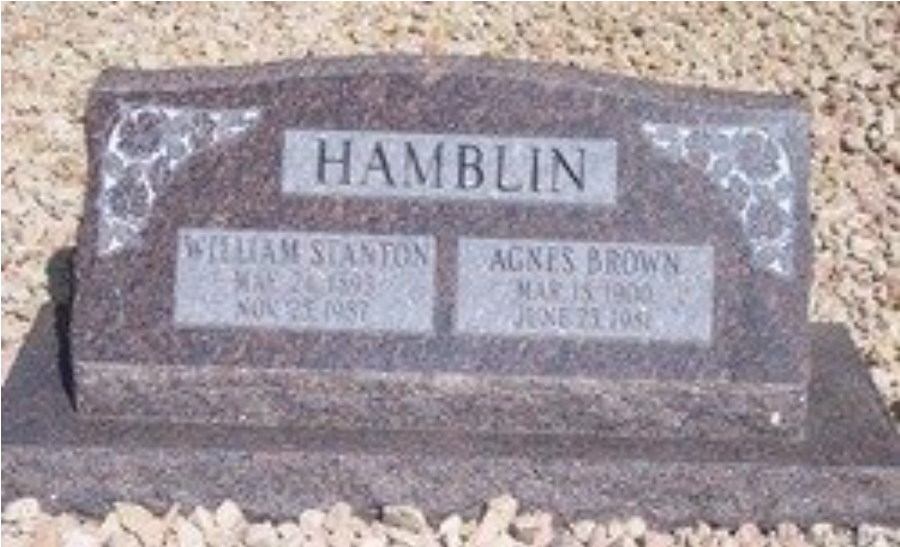

William Stanton Hamblin

May 24, 1893 –

Written in 1977

Brandon, the silver dollar that you got for your 12th birthday was given to your grandfather from his father, William Stanton Hamblin. Your grandfather hopes you will treasure it as a symbol of courage and faith.

My name is William Stanton Hamblin, born of goodly parents in Eagar, Apache County, Arizon, on May 24, 1893, at the Lytle home. My father was Jacob Hamblin, Jr., born in Santa Clara, Utah, March 21, 1865. My mother was Sadie Cornelia Lytle, born at Panaca, Nevada, October 16, 1867. They were married in the St. George Temple in St. George, Utah.

Life at that time was real difficult and hard to stay alive and to make a living for many was a real challang (challenge) for Father and Mother, not just their own family, but father’s mother, brothers and sisters, they provided for. In my Father and Mother’s family there was (sic.) 14 children – 9 brothers and 5 sisters - Jacob Perry, Lucy Priscilla, Wilford Woodruff, William Stanton, Jeremiah Roland, John Arlington, Sadie Alma, Carl Maeser, Velora, Lawson Arlo, Mark Elbert, Tannie May, La Vern.

Our first home was at Nutrioso, Arizona about two miles north of the town, a two-room log house. Father built a new home in town which is still in use, the Marion Lee home, built about 1895. I was a sickly child. Mother said she carried me in her arms most of the time, thinking I could not live much longer. Sometimes we do not always know (because) I am still around. They fed me on goat’s milk or anything they could me to eat and that was not very much because at that time, there was not very much to have, just what we could raise and find from Mother Nature, or we went without and that was quite often. Bread, milk, and gravy was (sic.) what we were raised on and we were lucky to have that.

My first memories as a child was (sic.) when I was three years old. My brother Roland came along about that time, pushing me out as the baby. Uncle Art Lytle was living at a ranch called Milligan between Eagar and Nutrioso, milking cows. He came over and got my brother Wilford and took him back to the ranch. I remember that I made such a fuss because I could not go. They locked me in a close (clothes) locker until I quit crying, then I would not come out. Father got me by the legs and dragged me in where Mother was.

I started to school at the age of six years. Maud Noble was my first teacher. I went to school dressed in a little checkered dress, made from an old tablecloth. And with long red curley hair. (Because) Mother had lost Jacob and Lucy, Mother said Lucy was a beautiful little girl and it was a real sorrow for Mother. I was kept as a little girl for a long time. I was small and rather puney most of the time, so I got a lot of attention from the family and from my teacher, Miss Noble. Some of the children felt like I was the teacher’s pet, and I guess that I was. She always called me her little boy friend so some of the boys nicknamed me, calling me little Maud, which followed me all the days of my life.

One day while at school I became very sleepy and Miss Noble sent me to play, but I went out and went to sleep by a red ant bed. The ants got all over me. I was so badly stung that I was not able to go back to school for several days. Mother said that I just about died.

One Sunday, my friend Drew Maxwell, who was my age, came over to the house while the rest of the family had gone to church. We found some matches and went out to make a fire. We had a large straw stack which the cows had eaten a hole back in the stack, so we got back in the hole, thinking noone would see us. We made us a little fire, but it soon became a big fire. We tried to get out but it was too hot. We started to cry and calling for someone to help us. Uncle Dudley Hamblin was coming out of church and seeing the smoke ran over to see what was wrong. He took off his new Sunday coat and beat the fire out and then got us out of the hot hole. His coat was a piece of roasted wool. Everybody was there by the time we got out and they all agreed that it was better to have a roasted coat than two roasted little boys.

Well, I was still in my checkered dress. One day, Mother needed something from a little store owned by Bro. William Pace. They had a dog that ran out and nipped me on the leg. I guess that I cred some, so Brother Pace took me in his little store, bought me a shirt and overalls and then cut my hair; he wrapped my long hair in my dress and sent me home. Mother would look at me and then cry. She kept those red curls until she died… we found them in her trunk.

Mother loved her family and tried hard to bring us up with high ideals to be decent and respectful. She would say to us quite often, “If you boys will neither drink or smoke, we will buy you a gold watch and chain when you are 21.” I think that it had some influence towards doing what was right, but they never had enough money to do the good wish that was in her heart, but I now wear a gold watch and chain and have for some 55 years, and I think of Mother’s desire to fulfill her promise many times when I look at the time.

While we lived in our first home, father took his mother back to Utah, leaving Mother and her children alone. It was a hard winter and father was gone for three months. We ran out of food, the snow was deep and no way to travel, only by horse. Uncle Will Lytle was living with us; he was just a small boy. Mother put him on a horse and with a letter to the Bishop asking for help, but the bishop refused to help her, saying to Uncle Will that he was looking after his own family and Jacob Hamblin should take care of his without asking someone else to take care of them. Well, Mother was desperate, her children was (sic.) starving. She prayed for help, then she thought of a man that was not a bishop and holding no part in the ward. He was considered a man of worldly ways. His name was Benjaman Brown; he was an uncle to Hugh B. Brown, so she sent her Brother Will with the same letter, pleading for some food and help. When Will came back, he had a large sack of flour, a slab of bacon, and a ham. Mother gave thanks to the Lord for answering her prayer. So what does it prophet (sic) a man if he has not charity? (So Benjamin Brown was a true Christian and a saint with mother. He was an Uncle to Hugh B. Brown.)

About that time, Mother took my brothers, Wilford and myself out in the pasture to fix a fence where some cattle had broken it down and was in our field. Mother tried to drive them out. There was a wild bull in the herd and was coming toward us. We tried to run but Mother kenw that it was a dangerous situation. She looked for some kind of protection. The rain had washed out a small ditch about three feet deep. Mother got us in the ditch, the Bull came over where we were, then pawed the ground and belloered a few times and then went back to the herd. I do not rember (sic.) how long we had to stay there, but I think we might of (sic) dug the ditch three feet deeper.

The first day of June was always a big day for country people and we young people always looked forward for the big events. Everybody that could go took their families (and) went out in the timber with big trees, made swings, played games and then a big dinner. For our last helping would be a jelley (sic) cake. The jelley (sic) was made from wild grapes and I think that it was the best cake that was ever made!

Most everybody had a(n) outhouse for a toilet. Some have had a three-holer, one for Mom, one for Father, and one for the little ones. While we were about ready to leave for the woods, there was (sic) three young ladies (who) went into the toilet. The door had a lock on the outside. My friend, Drew, saw the girls go in and we thought it would be real funny to lock them in, so we did. During the dinner hour, the girls were missed and someone went to look for them, they had been in the toilet about three hours. Well, the girls told on us and Live Brown (Eagar) caught us and I thought she was going to kill us, but I guess it was not more than we deserved but I thought it was at that time.

I was now in my 3rd year of school. At Christmas time, my cousin Ben Tenney and myself received a little slate in a red frame. I think that it was the best Christmas gift that either of us had ever received. Our Christmas was about four lumps of candy, 2 walnuts, either one apple or orange, 4 or 5 chalkey marbles. If we got a glass marble that was something wonderful. After Christmas, we were back in school. All classes held in one room. Each class would go up to the frunt (sic) for their lesson. This year, we had a new teacher, W.D. Rencher. He was real hard and crankey with the school (I thought so). One day, Ben and myself was doing something that mr. Rencher did not like. He came down to our desk and we had something on our slate that he did not approve off (sic.) I do not remember what it was, but he grabed (sic) both slates, broke them over our heads, leaving the frame around our necks, well, from then on I never had very much love for Mr. Rencher. Father ran the school, so Mr. Rencher did not come back the next year. (He was a good teacher for adults but not for the younger grades.)

About this time, as a little boy, I seemed to get into a lot of truble (sic), which I got paddled for. One day, I saw a man coming down the road in a one-horse cart. I hid under a bridge that he would come over, when he got to the crossing, I jumped out and threw my hat (at) the horse. Well, I gave him a good scare and he ran away. I thought it was real fun. Well, the man got his horse stoped (sic) and came back where I was, but I hid under the bridge. When he told me to come out, I knew that it was my Dad. I beged (sic) him not to hit me, I said, “Pa, if I had known it was you, I would not (have) scared your horse,” and that seemed to make it worse, and I got a good padeling (sic). At least Dad thought so, but I didn’t.

My sister Alma was the baby about one year old, when she sat down on a needle, went quite deep in her little seater. We tried to pull it out, broak (sic) it off. I held her with her little butty up so Mother could get hold of it with her teeth and got it out. Mother was sick and we did not have much to eat, some of the boys was (sic) going fishing and I wanted to go but did not have any hooks. Mother made me one out of a safety pin and I used a string for my line. The stream was small. I brought home three small trout. I do not remember wether (sic) I caught them with the hook, or got them wilth my bucket which I would use sometimes to catch the little minoes (sic) that was (sic) in the stream. Mother would say many years after that nothing ever tasted quite so good as those fish. (Well, that started me out to be a fisherman, now I am 84 years old and I am still trying to catch fish.).

At that time we had no doctors and everybody used what little knowledge and homemade remedy for medicine and cures. Someone had killed a small skunk which did not smell. Father skined (sic) it and Mother baked it for the oil that they would mix it with laudman and use it for earache. Mother had taken the skunk out and lifted it out on the porch in a pan. Uncle Dudley came in from the back and said, “Sadie, I hope you will not be mad at me, I have eaten most of that rabbit, and it was really good.”

I was baptized by Orson Wilkins in a mud hole and confirmed by my father.)

Father and Mother sold their property in Nutrioso and moved to Eagar. Our first home was a two large rooms log house; we only lived there a short time when Father built a new home. We lived there for about three years. Father had bought a farm so he sold our home to Will Eagar and built another home, which my brother Roland in later years bought and remodeled and is now living in it.

I was now 12 years old, real small for my age, and was always getting into trouble. Some of the older boys (in)formed me it was snowing that day and everybody was throwing snowballs. Someone said when the teacher comes out to ring the bell, we will all snowball him. I was for it in a big way, we made our snowballs and waited when he came out I wanted to be the first one to throw and then run. Well, I was the only one that threw. I hit him on the side of the head and knocked his glasses off. Well, nobody ran, and I was the bad boy. Well, school days were whipping days for wrong doings.

We raised our beans and ate a lot of them, and they had a lot of poopers in them. My friend, David Nelson, was three years older than I was. He had a girlfriend sit one seat ahead of him. One day my beans got to working and I had a pop-off. Well, I did not know what to do, so turned around, looked at David, and laughed at him. The teacher went down where he was, grabed (sic) him by the arm and said, “Young man, if you do that again, I will goifer (?) you.” His girl friend thought it was him (sic). Well, I knew what was going to happen after school, I got out first and ran, but not fast enough, Dave caught me and rubed (sic) my nose in the dirt. Well, I got a skined (sic) nose, and he lost his girl.

We had a small 20 (gauge) gun. I went hunting rabits (sic) one day. I got over in Mr. Hulsey’s field, the weeds were high and a big dog came running through the weeds. So I took a shot at him. I did not kill him, but he ran to the house yelping. Mr. Hulsey came out with his big gun and began to shoot. I thought he was shooting at me. He was not but I did not know it. I started to run and kept on runing (sic) until I got about one mile from the Hulsey farm and hid in a big wash and waited until dark before I dared to go home. But I never went hunting in the Hulsey’s field again. I guess that I was rather dumb and that I could never learn to keep out of truble (sic). One night the mail was late, we were all standing around waiting. We built a fire. Geo. Jarvis was there and told us that the old mail horses was (sic) scared of fire and they would really run and we wanted some fun or excitement. The mail came in; a poor old Mexican was the driver. Some of us threw sticks of fire at the horses, and my stick hit the old man on the neck. He began to holler, calling the postmaster, Mr. DeWitt. He came out but we had gone. I stayed out about all night, was afraid to go home. Sometime had passed and Mr. De Witt Alleck asked me about it and I told him what had happened. A few nights after that, we got into Mr. De Witt’s orchard to borrow some apples, I had filled my pockets and was crawling under the fence. Bro. DeWitt was there waiting for me. He handed me two more big apples and said, “Here, Stan, is a few more that you might need.” Well, I never stole any more apples from Mr. De Witt, and became one of my best friends. He moved to California. (Many years after that, he came back to visit. He told his son that Stan Hamblin was one to see.)

After school, one spring when I was 14 years old, I went to heard (sic) sheep for Mr. John Brown. We had 2 heards (sic). Charley Maxwell took care of the camp and was the cook. It was the month of May but we had snow and it was cold. Our camp was near the Ren Crosby Ranch, the head of Black River, just east of Big Lake. I had a mule to ride. At night, I would put my sheep in a corral, light some lanterns to keep the wild beasts away and then rid (sic) to camp. One night as I was saddling my mule, he broke away from me and ran. I followed him until dark. He went down a canyon. There was a long rope around his neck. He stopped by a big pine tree and I crawled up behind some logs and got hold of the rope, so after that I tried to be smarter than the mule. I tied him up before I put the saddle on. My brother, Maeser, and sister Alma was (sic) sick with scarlet fever. They came and took me back home. They were very sick and Maeser died. He was a boy in every way… healthy, good looking, well built and an athlete in many ways. It was very hard for Mother to give him up. She prayed for days asking the Lord to spare his life. One night while she was praying, she was given the feeling or impression that if Maesar lived, she would have a greater sorrow. His legs and arms were twisted and his brain had been injured with the fever. After that, she felt that the Lord had herd (sic) her prayers and was consoled with his passing.

I was paid for my work for hearding (sic.) sheep and I bought a cow and calf from Doctor Rudd. I had eight head of stock. Father never said anything to me about selling my cows and he let Uncle Waren Tenney have them and he never paid for them. Mother was very much upset over the deal and told Father that he would never get paid. Father would trust anybody, sighn (signing) notes which he would have to pay, and would give them anything he had if some would ask for it and people took advantage of generosity and on his death bed, he told me that he had to live a life time to find out that lot of things that he thought was (sic.) charity was (sic) nothing but ignorance and lack of judgement.

I was hit on the leg with a rake, leaving a bad cut. I did not take care of it. I got wet and the dye from my overalls got into the soar (sic.) and got blood poison in my leg. Mother and Grandmother Lytle used every home remedy they could think of, but I was real sick and was in a lot of pain. They became very frightened and worried. They put me in a buckboard wagon and took me to St. Johns. Grandmother Lytle came along trying to comfort or give me what help she could. A Doctor Platt was in St. Johns at that time. After looking me over, he said, “If you want the boy to live, his leg will have to come off,” but Grandma said, “No, if you take his leg off, he will die anyway, so we are going to bury him. He will have both legs on.” So they took me back home in Eagar doing everything that they thought might help me and nursed me back to health, and I have always thought the prayers and faith that Mother had that I might live with Grandmother’s love and care for me is one reason that I am still living and walking on two legs.

That summer after I was around and was back to normal, I got in a fight with Vernon Hamblin. I was getting the best of the fight and he set his dog on me. The dog got me by the leg and tore a big hole in the calf of my leg so I was sick with a bad leg for a long time, and I still have the scar from the bite. (Later on I got a chance to shoot the dog, and I did just that.)

Dad had bought a ranch in Greer in the spring before school was out. Dad took me to Greer and I was to carry the mail from Greer to Springerville and back the same day. I stayed at the ranch that Spring alone and I was afraid every night. A cow had died in the field not very far from the house. A big black bear would come almost every night and eat on the cow. I had a dog with me that stayed under the house. I always knew when the bear was around, the dog would bark and would go down where the bear was, and then the bear would chase the dog to the house. One night the dog was not fast enough to get under the house. He jumped on the porch and ran against the door, it came open, well, I might not be very fast, but I was fast enough to get the door shut before the bear came in. After that, I would put a nail in the door and put every thing that I could against the door. Sometimes when the moon was shining bright I could watch out of the window and see the bear and the dog going around and around.

Every other day was mail day, and one day I wanted to take a short cut and not go around the road. I knew of a trail that went down a steep canyon that we could go down during the summer when the weather was good. We had a lot of snow and the wind had blown over the bluff into the canyon causing large and deep snowdrifts. The weather had been cold, and there was a hard frozen crust on the snow. Not knowing the danger and risk I was taking, I got my horse out on the snow. The drift was steep, running down to the botom (sic) of the canyon. My horse stumbled and fell on the snow. I tried to get back but it was too late, we started to slide, roll and tumble until we got to the bottom, it must have been 400 to 500 feet from the top to the bottom. That was the reason we did not break through (the snow) (because) the horse was never able to get on his feet, he stayed on his side all the way down. I gathered things up and went on. I had to cross the river. I rode into the stream and water washed me from my horse. I could not swim but I managed to grab hold of a willow and got out. My horse had gone down the road without me. A Thompson boy saw the horse and he knew that something was wrong. He caught the horse and came back, about three miles before he found me. I was afraid to tell Dad, but I had lost some mail in the river that belonged to Mr. Cambell who lived on the river so he went to Mr. Becker who was the past Master about his mail. Father came up to Greer to see just what had happened. Mr. Cambell had told him that the trail was full of snow and he did not know how the kid got to the river. Father went down to see just what did happen. That drift was more than 100 feet deep covering some of the tall pine trees. It frightened Dad so bad that he forbade me to go there again until the snow was gone. Well, he did not have to tell me, because I relized (sic) if we had broken the crust we would have been there until Spring.

The family moved to Greer that Spring. We farmed, milked cows and made butter and cheese. I was the cheese maker. We would milk the cows at night and then in the morning strain the milk into a big wash tub, but we had to have the milk up to a certin (sic) temperature and put a white tablet they called rennut which would cause the milk to curdel (sic) or clabber. Mother would tell me what to do. She would put in salt and collaring (coloring?), and then I would do the rest. We would dip all the water or whey off, leaving what we called curd, then pour hot water over the curd, drain that off, then chop it quite fine, put it in a sack called cheese cloth, then put it in a wooden cog (?), put pressure on, to squse (squeeze) what water or whey might be left, and leave it to cure. This was done every day, six times a week, until we had enough for the winter.

That summer, we had a lot of chipmunks that would eat about everything and was (sic) a real pest. They lived in holes in rocks and trees. They would travel from the trees on our pole fence to our field and garden. We had a lot of fun trying to get rid of them. We would watch and when we would see them runing (sic) along the fence we would call the dog. Some of us would run down to one end of the fence and some to the other. They would stay on the fence trying to go back, and as the chipmunks came along we would knock them from the fence with a long stick. We killed a lot of them that way.

One day, father was out helping us. He got excited and was having fun with us. My brother Roland knocked a chipmunk towards Dad but did not kill it. It ran up Father’s pants leg; you would of (sic) thought a big bear was after him. He graved (sic) his pants where the chipmunk was and calling for help, we ran over where he was trying to get his pants off. We finally did. We shook his pants and found nothing but hamburger. Father had squeezed that little fellow so hard that it looked like it had been run through a meat grinder, and that was the last time Father tried to help us in killing the chipmunks.

I seemed to be the fisherman in the family, and it was part of our living. There was no limit at that time, and the streams and lakes was (sic.) full of fish. Quite often, I would take some of the fish with me when I took the mail and would sell them to a Mr. Holt who worked for Mr. Becker. He would give me 10 cents a pound and that was a lot of money, and the only money that I got from carrying the mail.

Father had a cousin Dewayne Hamblin. He was always saying what a good fisherman he was. One day, Father told him that he had a little redheaded freckled-faced kid to outfish him. Cousin Dewayne did not like it so Father bet him $25 (in the retelling of this story this became $100.). that I could outfish him. (That was a church bet which was never paid, win or lose), so the contest was on. The day was agreed on, the families got together and all went down on the river below the river reservoir for the big event and for a day of pleasure. And it was no laughing matter with Cousin Dewayne. He did not want a kid like me to be a better fisherman. The rules was (sic.) made, to start at the same time, stay close to each other and then stop at the same time. Cousin Dewayne had his two daughters, Wilmaith and Eva come along and count and carry the fish. Cousin Dewayne was a (sic) honorable man and wanted to play fair. He thought that we were even in numbers so he said, we will quit, but I guess that I was not quite as fair as Cousin Dewayne because I wanted to win and not let Dad down. At a bend in the stream, I had caught a fish that was not counted, and I put it in my pocket (the story later was told that Stan dropped it in his fishing boot) and not in my bag, so we went back to the camp and counted each bag. I had managed to put my extra fish in the bag with them not seeing me. When the fish was (sic) counted, I had one more than Cousin Dewayne. He laughed and said that your boy is not a better fisherman, he just outsmarted me. He was a good sport and many years after that he would talk about our little contest. He was a good man and a real friend to all of us.

It seemed like I was looking for fish whenever I had a chance. That Spring when we first moved to the ranch, I was walking along a filling ditch just above our house and I saw some big fish. I went back home and wanted Roland to go with me and maybe we could catch some of them. Roland had been sick and Mother did not want him to go with me, but she said, “Well, he can go, but if you get him wet, I will whip both of you.” We got some pitchforks and went down to the ditch and we worked until we got a real big fish in shallow water and then stuck it with the fork. It was one of the largest fish I have ever seen, a native trout, 24 inches long. We both got wet. I tied the fish on my belt behind me and we went home. Mother was really upset when we came in the house. I said, “Mother, I am sorry we got wet but could not help it. So I guess you will have to give me a whipin.” So I turned aroud, when she saw that fish, she was so excited that she forgot all about what she was going to do. I cleaned the fish and cut it up and the family had a big fish fry that night.

We always had a lot of things to do that we could enjoy ourselves. Life was never dull some time we would do things that Dad did not like and then life was not quite so bright. Father was gone most of the time, so it was up to Mother and we boys to run the ranch. Mother never did get very excited about things, so we were quite free when Dad was gone. We always had a lot of visitors. That was our social life, visiting each other. One night we had company, the wind was blowing hard, everybody talking and making a lot of noise. I had wind on my stomach and wanted to get rid of it. I opened the door, stuck my head out and pooped off, thinking that noone would hear me. I shut the door and said it was really blowing outside. Dad had heard me and he said, “Yes, my boy, it seems to be blowing inside, too.”

We moved back to Eagar that fall in time for school. I did not go to school that winter, I stayed out to plow, feed the cattle and sometimes carry the mail. One night, I went to a dance, I did not have a dance ticket so I stayed outside. The Church always had a dance manager, and he was sometimes called the breath smeller. Anyone that came in the dance hall that they thought might be drinking, they would smell their breath and if they smeled (sic.) whisky on them, they could not come in. Bro. Edman Nelson was at the door that night, when three men who had been drinking tried to go into the hall. Bro. Nelson tried to stop them, but he was no match for three of them. They got him outside and pulled his coat tail, pushing him from one side to the other, making fun, at least they thought so. Bro. Nelson had them arested (sic.) and brought them into court. I was called as a witness. Before they put me on the witness stand, the judge who was a Mr. Tony Long called out for me to come forward. He said, “Stone Hamblin.” I did not answer, he then said, “Stean Hamblin.” I still did not answer. “Stout Hamblin.” I still not answer. Mr. Long said, “What in hell is your name, anyway?” And everybody laughed. From then until now, I still have some of my friends call me one of the above names, Stean, Stone, or Stout. I guess I was about 14.

After testifying for Bro. Nelson, he thought I was his friend and I worked for him. Sometimes I stayed at his home that spring and carried mail from Eagar to Luna, New Mexico on horseback. I would go over one day and back the next. It was a hard trip about 50 miles each way, sometimes I would have mail stacked all over the horse that I could bearly (sic.) see out enough to ride. My lunch every day was a two large baking powder biscuits with a friend egg and a piinch of salt pork in each biscuit, but it realy (sic.) tasted good when I would stop and feed my horse and rest at noon. I would stay with Bro. and Sister Amasa Reynold, and we have always been good friends since that time.

My schooling was quite limited. Father and Mother always would say, you do not have good health and outdoor life is what you will need for a longer life. I do not remember graduating from the eighth grade. I was out of school so much that I just stopped going. When I was eighteen, I went to St. Johns Stake Academy, a church school, for three terms, but I was always from four to six weeks late in the fall, and then went back home a month before the school was out for the summer.

At this time, the draft was on for the Army. Wilford, Roland and John and I got my call. But I did not pass the exam. I always thought that I did, but somebody had to run the farm. I tried to volunteer and was turned down again. Well, I was not very large, I had to stand in the same place twice to make a shadow. I boasted 116 pounds when fully dressed with a few rocks in my pocket. We had a large farm and my father thought that I should know how to do everything, but I never did do many things that would please him. Well, that was the way I would feel at times, but maybe most children sometimes get in that mood.

We would plow with four horses, sometimes with two, but to plow 100 acres, it seemed like we was (sic) plowing all the time. Then plant it, mark it in small furrows, then to turn a small stream of water in each furrow so it would not wash was a job for an experienced man, but I tried, not because I wanted to, but I had to. When the grain was ripe, I would cut it with a grain binder that would cut it and bind it in small rolls, and then leave them on the ground. It took four big horses to pull this machine. After the grain was cut, we would gather the little bundles and put them in small stacks about 12 bundles to a stack, called shocks with the heads up. Then after the grain was dry we would load them on a wagon and haul them to a machine, called a thrasher, that would beat the grain out so the wheat or oats would run out of a small pipe into a sack, and the straw would go out another way to be stacked for feed for our cattle.

David K. Udall had the mail contract from Springerville to Holbrook. One day his mail driver was sick and he asked Father if I could go, I was only 15, but Father said I could go. It took four days to make the trip, two days down and two days back. We had a buckboard and two horses. Sometimes, just one horse and one horse cart. We would stock at Hunt, 30 miles north of St. Johns, camp for the night and then on to Holbrook. I had never seen a train. I went over to the RR depo (sic) to watch to see if one would come in. Sure enough, one was coming from the east and one from the west on different tracks, but I thought that they were on the same track, and I was sure they were going to crash. I got under a big box, and when I got out I was surprised to see them still going on the same track. Well, I went back with the mail for another trip. I went over to see the train again, this time it was a long freight train going along real slow. I wanted to ride on a train, so I grabed (sic.) onto the side of the train that had a lader (sic.) on the side. Well, it got to going quite fast, I was frightened and I knew that I had to get off as the train went around a curve, the grade was high so I let go and jumped off. I rolled, rolled, and rolled, but I did not get hurt.

Well, I carried mail, hearded (sic.) sheep, run the farm, but never did receive any money for it. However, I do remember Father giving me $1.00 for the 4th July. Father did not have a cash job and what little money we could get went for taxes and for family needs. He had his mother’s family and his to look after and he did good job in providing for so many.

Joseph Udall was our Bishop and our neighbor, and they were milking about six cows. They would turn them out on the streets and they were bad to break down or jump over fences. They kept getting in our field of grain. So one day, I drove them in our corral. I found five large five-gallon cans. I put some rocks in each can so they would rattle and then tied a can to each cow’s tail and then ran them out of the corral. Well, you can talk about the excitement it was! There half of the town turned out to see if the US Army had come to town. I was really having a good time, until I saw one of the Udall boys coming my way. He was four years older than I was. I ran, but it did not do me any good. I knew that I was going to get a beating, but he just set down on me and started to laugh. Then he said, “Well, Stan, do not do that again, but that was the best show that I have seen all summer.”

In the year 1812 and 1913, Father was building the Lyman dam, 12 miles south of St. Johns. He had gone on a bond for a Mr. Dave Rencher and WH Gibbons who had the contract to build the dam, but they failed and the state tried to collect the bond, but my father said, “I can not pay the bond, but I will build the dam.” And he did. He was able to pay all the bills and paid the men who had been working for Rencher and Gibbons.

I worked on the dam when I was not farming. I took care of the horses and helped in the cook shack some and kept time on the men. The dam was built with dirt hauled in on wagons about two yards to the wagonload. At first, we dug out a large deep ditch, then built a bridge over it so a team and wagon could drive under the bridge. The bridge had a hole in the top. The wagon was stopped under the hole. The men that was (sic.) driving and pulling a scraper called a fregno would fill it with dirt and then drive over the bridge and dump the dirt into the wagon. This was a very slow process so Father bought a machine called a loading grader. It took 20 had of horses to pull the machine, 16 in the front and four behind. It would plow the dirt and elevate it up so a wagon could be filled with the dirt from the elevator as they went along without stopping. Father was a good manager and he knew how to do things well and get along with the working men. However, I always felt that he was always on the other fellow’s side more than he was on his own. He was working about 100 men and he was carrying a heavy expense load so we could not have the work stop. A man by the name of John Hall was driving the grader with the 20 head of horses. He and Father were very good friends, but Hall was what they call a hot head. Father said something that he did not like. He jumped from the grader and said, “Jake, if you know so much, just run it yourself.” Father stood his ground. He sent someone after me. I went over to the grader and Dad said, “Stan, do you (think) you could drive that outfit?” I said, “Well I do not know, but I will try.”

Well, we got along very good and I thought I was a better driver of those twenty head of horses than John Hall ever was, and Father inflated my ego some by telling me that I wss a top hand. Well, you know that sometimes those good things do not always last, and if you alow (sic) your ego to become inflated too high, it might bust. Well, that was just what happened to me.

We had to get the dirt whereever we could. Father had cautioned me several times not to leave the grader in the hole where we were getting the dirt. Well, one day we had been working at the end of a dry wash, the hole was deep, we stoped (sic) for noon. We took the harness from the horses and left everything on the ground and went to dinner. Well, I could handle the grader and the horses well, and I knew that I could, but I forgot or neglected to remember Dad’s admonition and went off and left everything in the big deep hole. Well, while we were gone, a big rain storm came up and filled the hole covering the grader, wagons, harnesses and everything we had left when we went for dinner. And that was the last time we used the big grader. We spent sometime in diging (sic) a ditch to drain the water out of the hole. You could have called it a lake because in some places it was about 20 foot deep.

I guess that Dad thought that I was a better farmer than I was a dam builder. I was out of school that year and did not go back until the next school year. A Sister Wilbank that lived at Greer was runing (sic) a bording (sic) house for the school so I stayed there. It was the JT LeSuer home. He sold it to the church and moved to Mesa, Ariz. A man by the name of Sam Right had a barbershop just across the street. One day he was beating one of his boys, and I was standing by watching him. Well, I guess I was feeling sorry for the boy, and I said to Mr. Right, “You hit that boy again, we are going to beat you up.” He said, “You and who else?” I yelled at him and said, “Me, and all my friends here.” Well, he let the little boy go, but said nothing. About two weeks after that, I went into his shop for a hair cut. He took his clippers and cut a strip down through the center of my head and then said, “Stan, that makes us even.” He moved up into Utah but came back several times, and he would hunt me up if I was in town and would always tell me, “I have never whiped (sic) another child,” and would thank me for calling him some bad names, telling him what kind (of) a man he was. I do not remember just what I did say but I am sure that I was not a gentelman (sic) or a good Dad.

I was too small to take very much of a part in athletics, but did some long distant runing (sic). There was a contest being held at Snowflake, Arizona between St. Johns and Snowflake. Jess Lewis and myself wanted to run in the mile race but they thought that we were not good enough but said we could not be in the starting line but could run after the rest started. So we wanted to try. We got ahead of the other six that was runing (sic), but they underrated us. We kept getting farther ahead on each lap and on the last quarter mile they were quite sure that we did not count in the race and that we could not hold up at the rate we were runing (sic), but it was too late. So Jessie Lewis (2nd) and myself (1st) were first and second in the mile race. St. Johns won the contest and after we came home, the town was putting on a little celebration matching single men against the married men with various events. I was put in the ring with Judge A.S. Gibbons in a boxing contest. I don’t know why, unless I was always on the fight and would try most anyone that wanted to fight. Judge Gibbons was larger than I was, and I was somewhat afraid of him. I guess that I was not a very good sport, so I went after him with all that I had and broke his nose. It was never properly taken care of at that time and he always had a crooked nose after that. And I always felt that I was to blame.

During that time, if we wanted a little excitement or fun, if you might call it that, we had to stir (up) something ourselves, and fighting was one of the main events. And it was with your bare fists and no gloves and if a new boy came to town, he always had to prove himself in order to be excepted (sic) into the town boys. There was a boy by the name of Herbert Day that some of the boys thought that he was the best fighter and some of my friends thought that I was - at least they made us believe that we were. Well, Herbert and myself talked it over each thinking that we were the best, and so we agreed to go somewhere alone and try to see which one was the best. Well, we did just that and after we had pounded on each other, we stoped (sic) to rest, and decided that we were not getting any fun out of the fight, so we agreed to call it an even fight and went home.

I weighed 116 pounds when I was married.

(This is the end of this account of his life by Stan Hamblin. Later on, he shared with his family some other stories that are recorded elsewhere. Agnes wrote the following events and dates.)

William Stanton Hamblin

William Stanton Hamblin was born on 24th May 1893 in Eagar, Apache County, Arizona.

His mother’s name was Sasdie Cornelia Lytle, born on 10th of October, 1866 in Panaca, Nevada. Her mother’s name was Lucy Clarinda Atchison Lytle and her father was William Perry Lytle.

His father’s name was Jacob Hamblin, born 21st (22nd?) March, 1865 at Santa Clara, Utah. His father was Jacob Vernon Hamblin.

William Stanton Hamblin was blessed by L.J. Brown 3rd of August 1893.

Baptized by brother Orson Wilkins 7 July 1901.

Confirmed by his father, Jacob Hamblin Jr.

(Editor’s note: sic. means that even thought there was a grammatical error or spelling error in the original, it was left as it was in the copy.)

Death Calls Early Arizona Pioneer

On February 20, 1940, at Mesa, Arizona, death claimed “aunt” Sadie Hamblin , Northern Arizona Pioneer. She passed away quietly, after several months of suffering.

Sadie Cornelia Lytle, the daughter of William and Lucy Lytle, was born at Panaca, Nevada, October 10, 1867. She was married to a Jacob Hamblin, December 9, 1885 in the St. George Temple, Utah.

The young people spent the first years of married life in Pleasanton, New Mexico, but returned to Nutrioso, Arizona about 1878 or 9, where they made their home for many years, and where several of their children were born. Here her husband was bishop of the Ward, which then meant that he must keep an open house for any stranger or visitor who came into the town. Also that the condition of each member of the community must always be known to the Bishop. And it was the business and duty of the ‘Father of the Ward” and his good wife, not only to entertain, but help maintain and minister to anyone needing assistance of any kind. Thus it was that “Jake and Sadie Hamblin” became known throughout this part of Arizona, for their hospitality and especially “Aunt Sadie” for her kindness and helpfulness in sickness, trouble and death. She was a veritable “ministering angel” at such times, bringing hope and comfort by her calm and genial personality. The family later removed to Greer and Eagar. Here their last five children were born.

In 1914 when Jacob Hamblin was elected Sheriff of Apache County, they bought a home and took up their residence in St. Johns. Here the family grew to maturity and most of them married. They then removed to Phoenix and owned a nice home there for several years, and finally the last two or three years, resided in Mesa.

Sadie Hamblin lived during all the pioneer conditions incident to the colonizing of the Western country. Her husband …(blurred or not readable)… after outlaws who drove on the people’s horses and cattle, leaving his wife along long periods with little ones or the sick, and no help near. Often Indians or outlaws came to the homes of the early settlers and demanded food, or other things. Sadie was not a stranger to these circumstances and learned cheerfulness and self-control under all conditions. Her first home was a crude log cabin of the earliest type, her last a nice city residence with all modern conveniences, but it was always a real HOME, where her dear ones were assured of love and understanding.

She was the mother of fourteen children, ten are surviving, and nine were present at her funeral. They are Wilford Hamblin of Safford, Arizona, Stan Hamblin of St. Johns, Arizona, Roland Hamblin of Eagar, Arizona, John Hamblin of Mesa, Arizona, Alma, Mrs. Don R. Patterson of St. Johns, Arizona, Velora, Mrs. Harvey Ellsworth of Showlow, Arizona, Lawson Hamblin of Washington, D.C., Elbert Hamblin of St. Johns, Arizona, Tannie, Mrs. Carl Guthrie of Jerome, Arizona, Lavern, Mrs. Kent Pomeroy of Phoenix, Arizona. She also leaves numerous relatives, including brothers, sisters, nieces and nephews and grandchildren to mourn her passing.

Aunt Sadie has not been well since the death of her husband about a year ago. During his long illness, she remained at his bedside to cheer and comfort and minister to his every want, and when the end came, she found her own health utterly broken, and nothing in life to hold her. She seemed discouraged and felt that her life’s work had been accomplished.

Her children have given her every possible attention and consideration, but nothing could be done for her recovery.

Impressive funeral services were held in the St. Johns L.D.S. Chapel at 2 o’clock, February 28, 1940. The floral offerings were especially beautiful. Many incidents of her devotion to her husband and family, kindness and hospitality to strangers, the sick and needy, her faithful Church labors and her splendid management of temporal affairs, whereby her sons and daughters received more than ordinary educational advantages were related by the speakers. Those who spoke and paid tribute were Iris Hamblin Platt, Lorin Farr, Lee Roy Gibbons, Ed Greer, Gilbert Udall, Margaret J. Overson, Emily P. Udall and Myrian Brown. Sentiments were also read from Helena Naegle, Minnie r. Farr, Mary A. Richey, Melva Rencher, Susie V. Hamblin and Ella Greer.

Several beautiful musical numbers were rendered.

Interment was in the Eagar cemetery, where her husband and children, and many of her loved ones are buried.